Part I: From a Flood to the Cloud

Our winter program is hard at work this year. It’s a new year, and we’re not wasting any time. We’re building on the incredible and cool work we learned last year and putting it into practice to build capacity for our communities of Dyment and Borups Corners here in Melgund Township.

Jamie, Andrea and Ethan once wrote in a paper “It’s important communities have the tools, and skills, to tell their own stories.”

It started with a simple idea during our summer program: we wanted to support a local storytelling program. Thanks to the generous funding from the Ontario Arts Council and the Government of Ontario, we gathered for a series of weekly capacity-building activities focused on oral history, interdisciplinary arts, storytelling and learning to use digital tools. The goal was to learn how to document the voices of our community, to capture our experiences in Northwestern Ontario, and to preserve them. But we didn’t just learn to use digital tools. We also wanted to learn how to build our own!

When our community recreation centre flooded, it wasn’t just drywall and flooring that were ruined; we lost books. We lost physical records. We lost much of our tangible history. It was a stark reminder that paper is fragile. It molds, it tears, and it washes away.

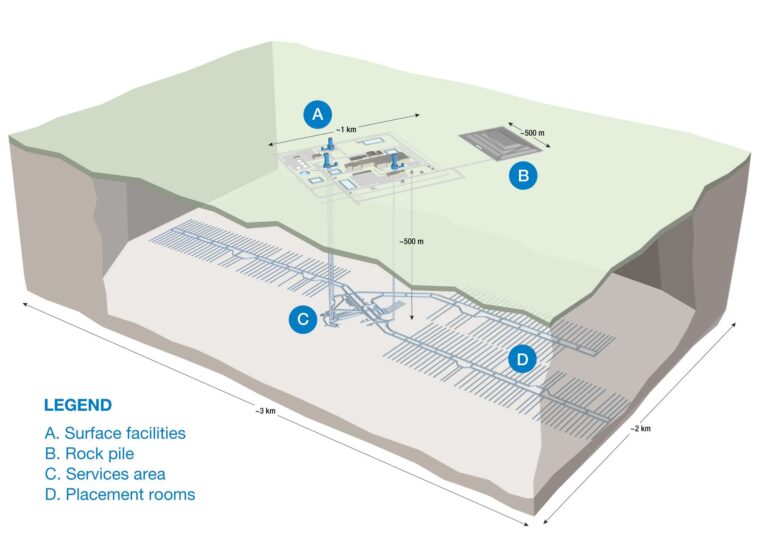

We realized that if we truly wanted to preserve our community history and stories, we couldn’t just rely on the physical world. We needed to go digital. But we didn’t just want to be consumers of digital tools—scanning pages into PDFs and hoping for the best. We wanted to be creators. We wanted to build the infrastructure ourselves.

Part II: Storytelling

We took a leap that not many arts organizations take: we decided to become a fully independent, digital publishing house. So we worked with our local Art Borups Corners collective, and several of our partners across many regions to amp things up.

This involved far more than just writing stories. We learned to code our own EPUBs (electronic publications) from scratch, ensuring our files were clean, accessible, and professional. But we didn’t stop at the creative side; we mastered the administrative side of the publishing industry as well.

We registered as an official publisher, giving us the power to issue our own ISBNs (International Standard Book Numbers). This might sound bureaucratic, but it is actually a smart move. Being able to issue our own ISBNs, we ensure that we retain full rights and ownership over our intellectual property and get rid of the southern gatekeepers. We are not listed as participants under a vanity press or a generic aggregator; we are the publishers of record.

We also learned to navigate the federal requirements for publishing. We successfully learned to handle digital legal deposits to Library and Archives Canada. This means that every story we create is preserved in the national archives. Long after we are gone, and regardless of any future floods, these stories will remain part of Canada’s permanent record.

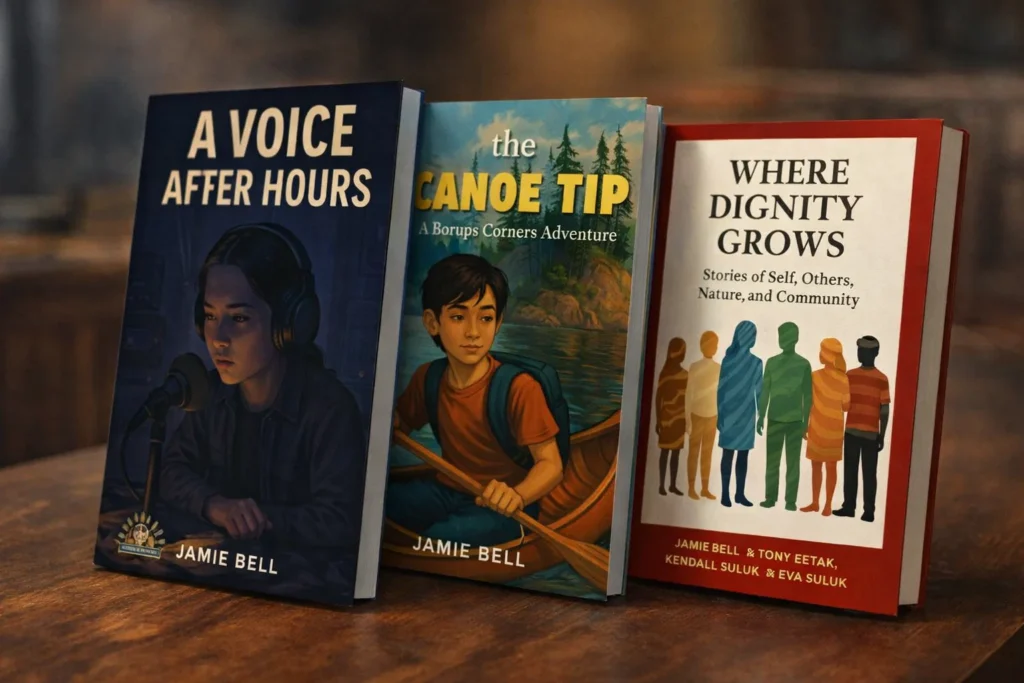

Look at what we achieved with the “Where Dignity Grows” and “Borup’s Corners Adventures” series. We took some fun short dignity stories and we put them on the world stage. We even got a shout-out in the House of Commons in October for our work on this project!

We looked at the data, and it is humbling. The Weeds and Walls is available at Barnes & Noble in the United States and Librarie E. Leclerc in France. Tony Eetak’s Eddie’s Secret Box can be found on Bol.com in the Netherlands and Apple Books. Eva Suluk’s The Quiet Bird on the Sill is listed on Thalia in Germany.

We saw our stories travel to places we might never visit physically. The Sakoose Compass made it to Rakuten Books in Japan and PChome 24h in Taiwan. We saw The Pixel Mask available at Casa del Libro in Spain. From the Palace Marketplace for libraries to Indigo Chapters, Apple Books and the Library and Archives of Canada, the digital infrastructure we learned to navigate allowed us to “flood-proof” our culture. These stories will never be lost again. They are also replicated on servers across the globe, safe, accessible, and fully owned by us.

Part III: A Tool for Reading

While conquering the global bookstores was a triumph, we faced a different problem here at home. We had all these beautiful digital files and tonnes of stories, but the technology to read them was proving difficult to the very people we wanted to reach: our Elders and community members. The issue is that many people – including adults and youth, simply have no ability to even read an online book or publication.

Modern e-readers and commercial apps can be difficult for people who don’t use technology a lot. They are often filled with advertisements, complex “storefronts,” confusing logins, and buttons that are too small to tap. We watched community members struggle to open a book on standard tablets, getting lost in settings menus or accidentally purchasing things they didn’t want.

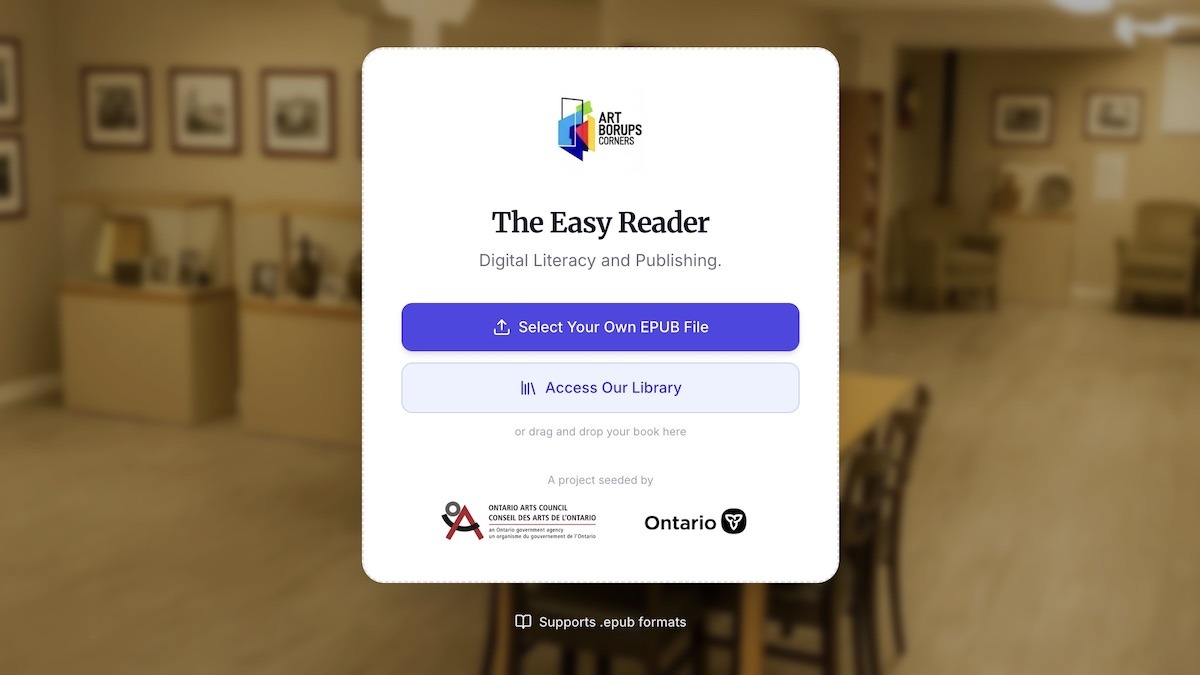

This summer, we developed “The Easy Reader.”

We designed it with a philosophy of radical simplicity. We stripped away the noise. There are no ads. There are no “customers,” only readers. We built it specifically for mobile, tablet, and desktop, ensuring that it adapts to the device, not the other way around.

We focused heavily on accessibility. We added a “Sepia” mode and a “Night” mode because we know that harsh white screens hurt tired eyes. We built a text-sizing engine that allows a user to scale the words up significantly without breaking the layout—a crucial feature for our seniors. We chose specific fonts, like Lora and Merriweather, that are designed for long-form reading comfort.

But the most important addition was a new “Library.”

We didn’t want our users to have to fumble around with file managers or downloads folders. We saw a lot of people struggle to figure out just how to load a file. We built a direct connection—a “Library” button right on the main screen. When clicked, it opens a sample curated selection of our stories, stored securely in our own cloud bucket. A user sees a title, like Mona’s Secret Songs or The Canoe Tip, and with one single tap, the book opens.

It is a curated space where the technology fades into the background, and the stories takes center stage.

Part IV: Arts and Tech for Literacy

This project was, at its heart, an interdisciplinary arts project. But usually, when people say “interdisciplinary,” they mean mixing music with painting, or dance with poetry. We took a different approach. We mixed oral history and storytelling with software engineering and publishing administration.

We discovered that coding is, in itself, a form of storytelling. It is a language with syntax and rhythm. By building our own digital infrastructure — from the ISBNs to the EPUB code to the Reading App, we were essentially building the stage as well as writing the play.

This is an incredibly advanced approach to storytelling, especially for a group in Northwestern Ontario. Often, arts groups in the North are expected to be consumers of technology: We buy the iPads, we download the apps, we use the platforms Silicon Valley gives us and southern people usually take all the work.

In this project, we flipped that narrative. We became the architects.

We are incredibly proud of what we have accomplished.